- Creativity for Good

- Posts

- turning research into child's play

turning research into child's play

creativity q+a with val weisler

When most people think of academia, most of the time what comes to mind is libraries, lecture halls, and old white professors in tweed blazers.

We don’t, generally, think of creativity. When we do associate creativity with academia, it’s because we’re thinking about traditional “creative” degree programs —MFAs, maybe, for visual artists and creative writers and performers, or even PhDs in literature or fine arts or theatre.

But creativity, we know, shows up everywhere — even in the dusty halls of academia. Which actually, it turns out, aren’t always (or even often) so dusty.

For this month’s creativity Q&A, I chatted with Val Weisler, who knows all about the ways that academia, research, and education can be creative in unexpected ways. Val is an activist, a kindness and positivity educator, and, most recently, a PhD student studying Children’s Rights — and she’s an expert in taking what people think of as “academia” and turning it upside-down.

creativity q&a with val weisler: listening to your inner child

Shelly Jay Shore

Tell me a little bit about who you are and what you do.

Val Weisler

So, I live in Brooklyn and in Belfast, which I'll explain in a second, and I am a PhD candidate in Children's Rights at Queen's University Belfast. Queen’s University is the only university in the world that has an entire center for children's rights, full of children's rights experts that you can do a master's or a PhD in.

Shelly Jay Shore

What does it mean to get a PhD in children's rights? Like what does that look like?

Val Weisler

So it's kind of funny, because I'm the first American to be answering that question. So, there has never been a Doctor of Children's Rights who's an American. So if all goes well, and I graduate in two years, I am going to be the first American Doctor of Children's Rights. And it's very much rooted in the fact that the United States is the only country in the world that hasn't ratified international children's rights, so it's really like a very lesser known field here. For me, my PhD is focused on a child's rights specifically to seek, receive, and impart information, which is known as Article 13 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (the UNCRC).

So I'm focusing on a child's right to information in the US, arguing that even though the US hasn't ratified the UNCRC, children still have a right to information through the First Amendment, and also through the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which the US has signed on to, which talks about the right to information.

My focus is looking at what child friendly material would look like if children were actively involved in designing it. Currently, on a mainstream level, children aren't involved — or are only very tangentially involved. Usually, whether it's about a social justice issue or it's about a resource in a child's area or it's a mental health topic, whatever it is, especially outside of the traditional school system, a child is handed what an adult considers to be "child-friendly" material. And that's a flyer that has 80% of the information stripped away. It's in Comic Sans and there's a picture of a giraffe. And the giraffe has nothing to do with the content, but it's there and thus it's child friendly.

Shelly Jay Shore

Of course. Love a giraffe.

Val Weisler

Totally. So in my masters, we looked at examples of adult-made "child-friendly" material. And of course, a child can't know that they have rights or know about any of the resources that are available to them if that information isn't accessible. Currently that information isn't available, because the only child-friendly material that organizations and governments and NGOs and community centers are saying that they have is a one-sided piece of paper that is usually somewhat condescending towards a kid and doesn't actually give them the information they deserve.

And what's on those materials is all based on an adult's assumption of what a child can handle learning about. So my PhD focus is going to be working with a group of twelve children, ages five to eleven, who will be my co-researchers at the Brooklyn Children's Museum. I'll work with them to have them design their own child-friendly material on children's rights that I will then have another group of children come in and interact with.

And through observations and interviews, I will be learning about the differences in child-friendly material when a kid designs it versus an adult, and the differences in a child's experience interacting with child-friendly material that was made by a peer. And then I'm hoping to use those findings to work with my child co-researchers to develop the first manual for how to make child-friendly material that's actually informed by how children want to receive information.

Shelly Jay Shore

That's so cool. And I'm glad you brought up the work you're doing with the Brooklyn Children's Museum. Can you talk a little bit about what your role is there and the kind of programming that you're doing?

Val Weisler

Totally. So, I'm there as a school programs educator. Some background that might be important is that I'm a first-generation college student. I was the first person in my immediate family to get a four-year degree, so then getting a Master's and getting a PhD has all been just such a new experience. When I got my Master's, the idea of a PhD was very far off — it was like a maybe, but like transparently I didn't really know what a PhD was, I just knew that like my professors had them. I didn't think I was going to do a PhD. And then at the end of my master's, my supervisor asked what I was going to do next, and I was like, "I think I really want to work at the Children's Museum in Brooklyn, I went there as a kid, my mother went there, my grandfather went there, I'd love to work there. But I'm also really interested in how children would design child friendly materials so maybe I could be at the museum and I could work with some kids there like informally, and I could see what they do!"

And then she was like, "You're describing a PhD. That's a PhD project." I was like, "That's a PhD? Like, you just get to geek out over what you care about for a couple years? Like, oh my god, okay, let's do it!"

So I applied and I was able to get this full scholarship that lets me do this, but for a year before that I got a job as a school programs educator at Brooklyn Children's Museum. I've worked there now for almost two years, and my job is teaching classes for children that come in on school or camp field trips. So they come in on a visit to the museum as a group, and I'm either showing them a lizard and making having them make a tiny habitat for their own imaginary animal, or I'm showing them a hat from 200 years ago or a necklace from 20 years ago, and then having them make their own adornment that they can decorate themselves.

Usually it's something like showing an object and being able to have them interact with it and then conducting some sort of an art project. And getting to do that for the past year and a half has been really instrumental for my work in my PhD, because I always want to make sure that as deep as I get into the research of children's rights that I'm not that's not suddenly distancing myself from being on the ground with kids.

And through that I've also kind of gotten to see children's experience after interacting with adult-made child-friendly material on a day-to-day basis, and think what it could look like to be able to have them be more of the behind the scenes creators of the things that their peers will get to create or be interacting with later on.

Shelly Jay Shore

One of the things I talk to other creators about a lot of the time is what it feels like when creating things like feels like play, and how enjoyment comes into it. There's like, there's so much psychology behind getting into that state of like play and wonder and enjoyment of what you're doing. And so much of what you're talking about is so creative in terms of the way you're asking questions and the way you're thinking about like, how are kids gonna approach this? How are kids gonna interact with this? How are they gonna experience it?

Val Weisler

Yes, exactly.

Shelly Jay Shore

How does that sort of process happen for you? How does something go from being like an initial idea to being like a presentation or an educational program, both for kids, but also for adults? Especially since I know that part of what you do — part of what anyone in academia has to do, I guess — is also to talk to adults about all of this.

Val Weisler

Yeah, that's a good question. I think a lot of it is like thinking about how I can turn something on its head a little bit, kind of like messing with the power dynamic and messing with the way that information is usually distributed. So, whether it's to the children that I'm working with or going to work with, or it's to adults about children's rights. And whether you're a parent or you're an educator or you're an academic or, you know, an activist, like however you are, I try to put the focus on what it looks like to be in relation with children. I think often about when I'm working with adults, I'm focusing on what it looks like to curate a space when I'm talking about these things that are simultaneously for them as an adult who will be in relation with children, and also for their own inner child.

And I think that those are so much more bonded than we think. And I think that it's really interesting. There's a lot of language, especially in the past few years about healing your inner child. And I think that part of that is also like remapping how you operate with kids. The way you think about them and the space that you foster for them directly impacts, in my opinion, the way that you're thinking about the kid that's inside of you.

So I think I have a lot of experience with this being a first generation college student. For me, it's kind of been the reverse of it, where a lot of my own experience is like receiving information that's supposed to be really inaccessible to someone who doesn't have a parent who is, you know, an academic or a professor or some college coach, someone you can call up and find out, like what do office hours mean? How do I do this? So I had to make it accessible to myself. And I think that that's kind of fueled me in this as well, because I have the experience of having to like line up all the Vals who are getting a college degree, master's, PhD, whatever, and think about, "Okay, I'm 18. How do I explain to nine-year-old Val what we're doing? I'm 26, how do I explain to 22-year-old Val what we're doing?"

And I think that that kind of translates into the way that I go about talking about this, whether I'm on my Instagram or leading a workshop. And I think the same goes for working with kids on the ground. Thinking about next year when I have children I'm working with, I won't just be interviewing them, I'll be working with them as my co-researchers for a few months. So I'm constantly thinking about, you know, how do I recognize that I inherently have this power over them as an adult, as a researcher, and how do I mess with that?

You mentioned the word play, and I think that's what I really try to do — to look at the way that this would usually go and think about how I can flip it. For example, working with kids as my co-researchers, like coming in as a researcher but like having a Ms. Frizzle fashion sense, like all of the things that I hold deeply to me as a person are also serving me. And doing this because I think that a lot of adults hear words like "academic" or "PhD candidate" or "children's rights'' and get a little bit spooked, like, "Am I gonna find out that I've been messing up my kids?" Or, "Am I gonna not know what you're talking about with this government document?"

Like, suddenly people feel really incapable. And it's like, I know that feeling! I've been in the room where people are talking about things and I'm like, "Shit, I don't know how to do this!" It's being 14 in a room full of 30-year-olds, or, you know, I'm a freshman in college and everyone else as a parent they can turn to, etc. So I think I kind of take that into the spaces with adults and kids. For my masters, I was working with teenagers, and I interviewed them on bean bags. And I knew that like the way to get them to be most vulnerable with me was to build that trust, so I went to the mall with them and after like three hours at the mall and eating burgers and having soda together, they started to tell me about how they were writing a manifesto to the United Nations. And I was like, "okay, we're getting somewhere!"

And I think the same thing goes for adults with their inner children, and the children I'll be working with who are actively in childhood. It's a lot of trying my best to de-hierarchize the power that I have in that room, and really peel back the layers of children's rights to be what it is — which is something that actually everyone has experienced, especially experiencing the lack of it. It's meeting them there with that, and then like building it out in a creative way to be something that we're not just memorizing or reading and feeling intimidated by but actually interacting with and getting to apply to our own lives, whatever age we are.

Shelly Jay Shore

I love the idea of play as a destabilizing equalizer. Like, we're taking away the associations that people have not just with academia, but like with research — like, I think when people think about academic research they think of libraries and PDF annotations. Even, you know, qualitative research, people think of folks like going in and doing in-depth interviews in a very formal way.

Val Weisler

Very formal, exactly.

Shelly Jay Shore

So it's very different to think about it in this kind of sense of like, how do we turn that on its end, not just to get into what we're learning, but also to create an environment where your co-researchers are comfortable. Rather than saying just, like, "this is Val, she's in charge!" Instead it's, "This is Val, and you're her co-researchers." Not in a patronizing, therapy-language sort of way, but genuinely saying, "You're the expert. You're the expert in your experience."

Val Weisler

Yes!

Shelly Jay Shore

"I'm the expert in this particular academic situation, but you are the expert in being five."

Val Weisler

Literally, yes! Like I don't know what it's like to be five right now. I don't know what it's like to be five in 2024. And especially working in Brooklyn, I'm also obviously very passionate about making sure that I work with a diverse group of children and ethnicities, and the areas they're coming from and their abilities and their income statuses.

So there's so many layers to how they are the experts. And I think what you touched on about therapy language is actually so true. So much of working, in my opinion, with anyone as a researcher, but especially with children, is using some of the same tactics that therapists use. Like, excuse my therapy fan geekiness, but I've definitely leaned into what it would look like to be a child therapist. Like, how am I curating a space of trust?

A therapist has a power dynamic, so how am I taking that off? How am I utilizing play to be able to forge this bond? How am I recognizing that like the main way that a child communicates might not be speaking?

That's something that really comes up with working in therapy with children. And I know it because I lived it. Like, you're handed a piece of paper and you're told to draw your experience or you're given some play or some dolls and who's good and who's bad in this situation. And something that I try to emulate when I'm working with children in this way is like recognizing that they're the expert of whatever age they are, and that doing a formal interview isn't gonna serve anyone because that's not the way that they mainly communicate.

Like art research, which is one of the methodologies that I'm gonna be implementing, is most useful because that's the way that they have the most experience communicating with each other. So maybe we're doing a puppet show where we talk about what it means to be listened to, and examining how it feels when you have information to share.

Like that's actually most useful for them because like they're like, "oh, like this is like when I'm on the playground, and yeah, like, okay, I can do this!" So I think that that's really helpful to be working with kids. And I actually think that the same goes for adults. Like, when I work with adults and we talk about this, the time that I see it hit the most and that they really internalize it the most is when we take apart the normal structure of like, I'm gonna lecture you and we're gonna read this 20-page document.

But instead I'll frame it like, I want you to think about when you were a kid. How did you know what it meant to be listened to? Do you remember ever interacting with child-friendly material? How did it feel?

Did you ever know that you had rights as a child in the United States? Like, I think it really is about channeling inner child me and thinking about the different ages that are at the table and how whatever age they are, we can all take the toolbox from a kid because it's actually the best way to learn and to dive into this.

Shelly Jay Shore

So I'm glad you brought up how you present these concepts to adults, because I think that's so important as well. Can you talk a little bit about a program or a presentation that you did where you were able to bring that perspective — that kind of equalizing, turning-it-on-its-head approach?

Val Weisler

Yeah, I mean, I just presented for the first time at an academic conference called the Children's Rights European Academic Network, and it's a network of about 30 universities that all have children's rights programs. And that was my first-ever academic conference that I was attending, and the first one that I was presenting at, and it was all children's rights PhD students so it was such a cool experience. And I was only American. But I presented on my research, both what I have found so far in my literature review and what studies exist and what they're missing, what I hope to fill and then also what I'm planning to do with them for the future doing my on the ground research.

And I knew that going into this conference it was very much the formal traditional way that it's planned out, where it's like, you're presenting for 10 minutes and then you're going to be on a panel with two other people that presented, and there's going to be a senior researcher and they're going to decide what questions you're asked and what feedback you get. And it was a very cool experience but it was very traditional. And I really felt the urge to be like, "How do I mess with this?"

So I talked to the two other people that were on the panel, and I asked them if they would be down to include a photo of us as a child on the first slide for each of our presentations, and to take a minute before we went into the presentation to talk about who we were as a kid. Because all of us had this strand of working with children, we're all going to work with children in collaborative ways, so like, what does it look like to set the foundation of, you know, "This is me when I was a kid, and there is a kid in all of us still, even though sometimes we forget." And I think right off the bat that really shifted the energy in the room, because you're at this conference where it's very professional, and you're supposed to network, you're supposed to be sharing your title and your research. And it's like, this is children's rights! Are we really ignoring the fact that like, I played with the dirt or you know she put a worm up her nose?

Shelly Jay Shore

This is professor so-and-so, it's okay to acknowledge that he probably ate glue!

Val Weisler

Yeah! And it's like, what does it look like to actually like to recognize that, especially in children's rights, where we talk a lot about a child's capacity, what does it mean to bring our own inner child to that work, to remember what it was like to still be that child? Because no matter what a child's capacity to exercise a right is, they still have that right.

Like we talk a lot about baby's rights. And like, even if a baby can't talk, they still have the right to an education, the right to play. And it's up to their caregivers and the adults in that community to be able to advocate for them, but they still have the right.

So I think that that set it up in a way that was different, and kind of broke the ice of being able to talk about working with children as co-researchers. I saw like people's faces soften and saw them start to think about who they were as a kid as well. Children's rights in general is still somewhat of a new field and it's definitely more of a radical field all in all, but even there's still these assumptions and these varying opinions, and there's people in the room that are like, "We should still be making the decisions for children." And I think including the photo and then talking about children as co-researchers and really focusing my my presentation on this idea of like, "This is what I'm going to do, and here are my research questions right now but like my my co-researchers could change them, and here's the way that I want children to interact with what they create but my co-researchers could decide that actually we should be doing something else." They're going to create their own child friendly material, and I don't know what they'll make.

Like, maybe they will make a flyer! Maybe it'll even have a giraffe on it! But also maybe it'll be like a singing dinosaur or a puppet show or a movie, like I truly have no idea. I think that I'm really grateful I did it that way, because especially in academics you're taught to put on this face of, like, I know everything, and I am the expert, and I'm gonna find out the Right Answer. And part of children's rights is seeing children as rights holders and as people and human beings. There's this phrase that I really love, which is that "children are beings, not merely becoming." And part of that is recognizing that like I alone, without the children I'll be working with, can't really speak that deeply on my research because I need to consult with my co-researchers.

And I'm grateful for that because I think that that's the start of dismantling the hierarchy. I think we have to recognize the both-and of working with kids, which is like, I'm going to be working with 12 kids and they're gonna be kids. And they are the expert of their age and they know how they want to receive information and they know how they want to give it, and part of the right to information is being able to sit down with them and find out what they think instead of thinking that I as an adult know best for these kids, when they're the ones that are day-to-day living their lives as who they are. So I think that that starts with the messing of it — just recognizing that there are inherently voices in the room, and we shouldn't be making decisions without children speaking on their experiences and what they need and how they need it.

Shelly Jay Shore

Well, I want to read every piece of research that you ever publish. I will be taking all of it into account in my parenting and my general existence in the world.

Val Weisler

You're doing great.

Shelly Jay Shore

Aw, thank you. So, what's next for you? What is coming up that you're excited about?

Val Weisler

So I am gonna be spending three months in Brooklyn, and I'm really, really excited about that. I am currently working on designing children's rights classes that I can offer online and in-person in Brooklyn over the next couple months that work to dismantle what we're usually taught an academic class would look like and be able to work with adults and have play involved and have children's voices involved. So I think that that's what I'm most excited about for the next chapter.

Val's passion for children's rights started when she was a child herself. As the founder of The Validation Project, Val has spearheaded a global movement to empower young people worldwide. Now a Department for the Economy funded PhD Candidate in Children's Rights, Valerie currently explores a child's right to seek, receive, and impart information within the United States—the only country that has yet to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Val's research explores what child-friendly material would look like if children were actively involved in its creation and dissemination. Her PhD project will be the first-ever study about the right to information to involve young children as co-researchers. Follow her adventures on Instagram at @valweisler.

updates from shelly

Exciting news: we are just 50 days away from the release of Rules for Ghosting! I can’t believe that this book is less than two months away from being out in the world. If you haven’t preordered yet, there’s still time — get your copy at your favorite retailer!

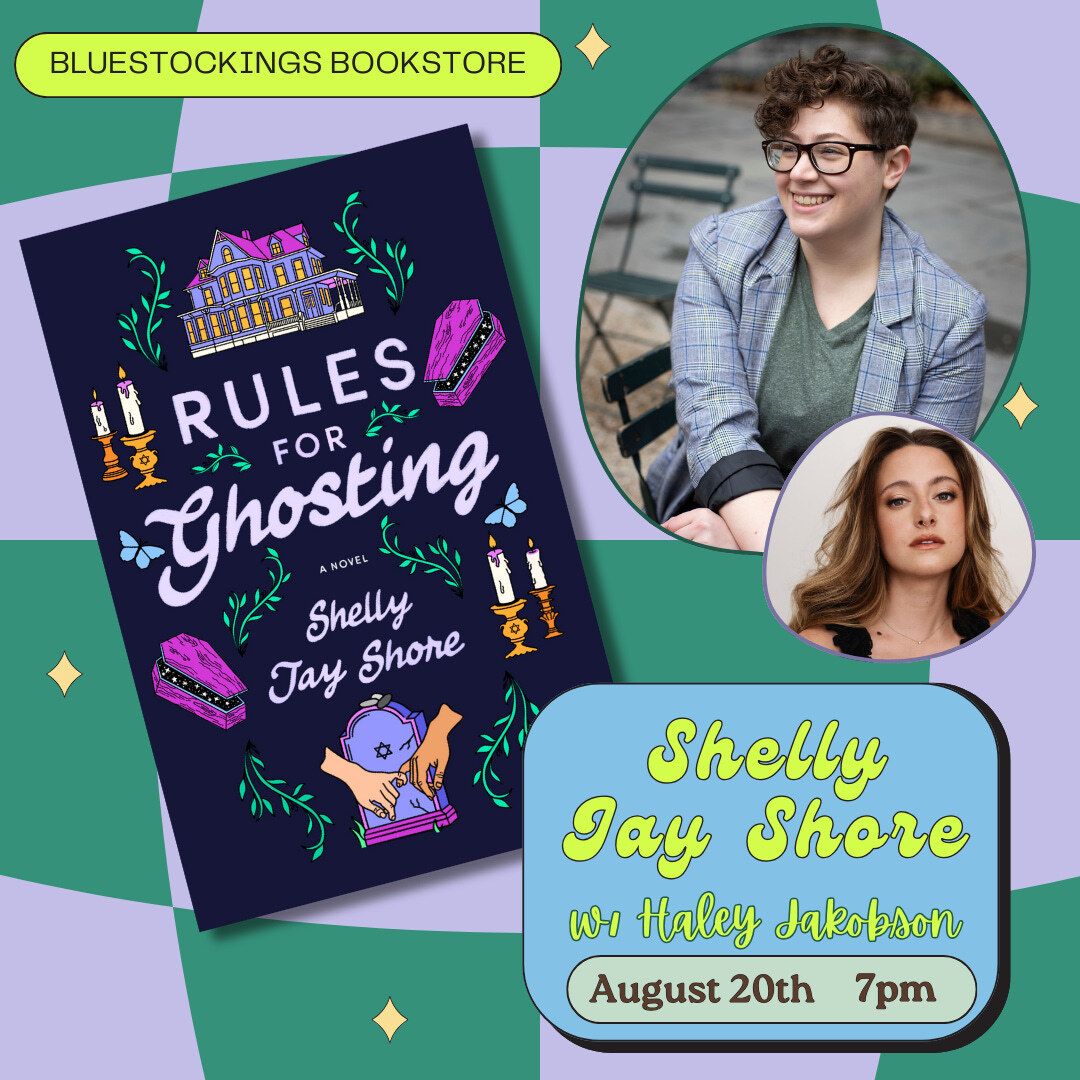

Also, #ICYMI: We’ve got a launch event on the calendar, bay bee!

I’ll be at Bluestockings Bookstore with the incredible Haley Jakobson, chatting all things gay, ghostly, and bookish. Tickets are on sale now, and the price of admission can go toward a copy of Rules for Ghosting — I’ll be signing them after my talk with Haley! Please note: Masks are required at this event. We keep each other safe! 💜

resources, links, and further reading

spotlight on: children’s rights and creativity

read / watch / listen: “‘Listen to us’: Children deliver their manifesto for World Leaders and call for safe-space education for all” at the Lego Foundation

read: “Creative Expression: Are Some Kids Missing Out?” by Joanne Foster, EDD for The Creativity Post

donate: The Brooklyn Children’s Museum (Val’s pick!)