- Creativity for Good

- Posts

- 💜[12/26] the creativity for good friday five

💜[12/26] the creativity for good friday five

this week’s highlights on creativity for good

We made it: today is the last Friday Five newsletter of 2025!

When I committed to this weekly cadence back in September, I really wasn’t sure how it was going to go. I’ll be real with you all — I’m actually a little bit shocked that I got us here, and actually stuck with an every-week habit (that one post on a Saturday doesn’t count, air travel is nonsense).

To be fair, I didn’t actually follow through on all the commitments I made in that letter; specifically, y’all have only gotten one Creativity For Good post in the past few months, and even though I have two Creativity Q+A interviews waiting for transcription, I haven’t gotten around to sharing those, either. But given what 2025 has been like on the whole, I think we all deserve a gold star just for still being here. Don’t you?

The Vibe

“You did it” has been my mantra the last few weeks of this year. There’s a sticky note that lives on my desktop that reads “JUST GET IT DONE” — and, too often, that’s about how I’ve been getting through each to-do list. Just do it. Just get it done. Do it perfectly if you can, but you probably can’t, and that’s okay.

As we head into this last week of the year, here is my wish for you: Whatever is left on your to-do list, whatever really can’t just wait for the turning of the year, just get it done. But if it can wait, let it. We may be past the solstice, our days slowly starting to lengthen, but our hours of daylight are still short, and the nights are long, and our hearts and bodies are looking for rest. So take some, if you can.

See you in 2026, dear ones.

your friday five!

this week’s highlights on creating for good

”Picture This: You’re a Frog” (Alex Manley for Hazlitt)

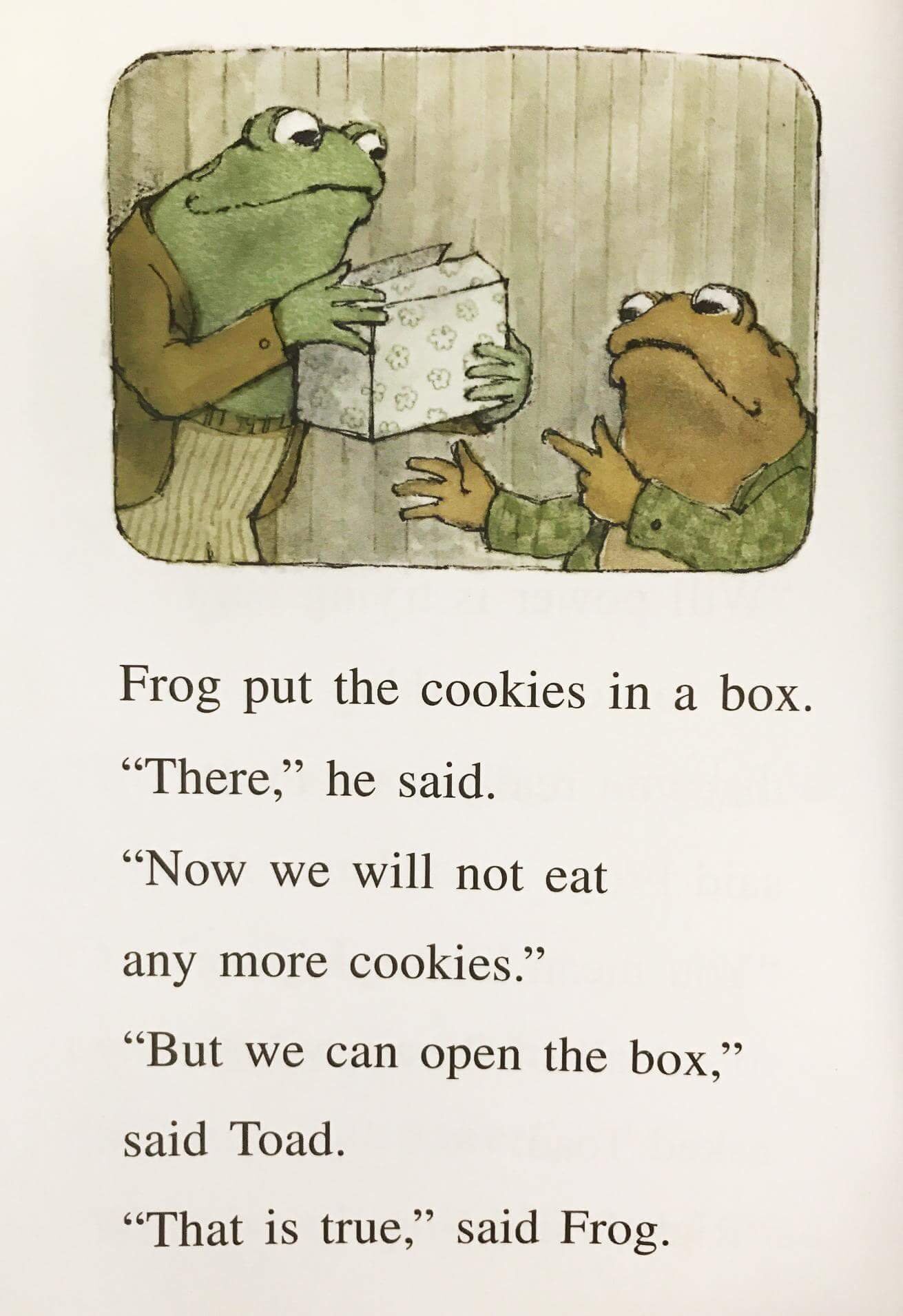

My kids are really into Frog and Toad right now. And honestly, who can blame them? Frog and Toad are, let’s be real, Goals. Friend Goals, Husband Goals (yes, Frog and Toad are gay), General Vibe Goals. I mean, come on:

it me.

The wouldn’t it be nice whimsy of Frog and Toad comes up in Manley’s lengthy (but worth the read) rumination on “frogposting” — that genre of posting that’s centered around the fantasy of taking off our People Hats in order to imagine the sort of pastoral simplicity of life as a little woodland creature: an insect, a frog, a mouse, a duckling. Frogposting, Manley writes, differs from other exercises in nostalgia by its intentional separation from capitalism and corporate entities:

The frogposting mode is fascinating because it’s seemingly embraced primarily by the hyper-diverse and accepting youth of today despite its inherent backwards-looking qualities. The people making and liking these posts are not imagining being bugs and frogs and woodland mice in a far future, after capitalism (having sown the seeds of its own destruction) has finally collapsed; it’s an imagined past, a pastoral imaginary — or perhaps, in especially 2020s fashion, an alternate timeline in the multiverse.

[…]

Frogposting is also more interesting, creative, and funnier than some of the other genres of nostalgiaposting: for instance, the “It’s 2002. You’re logging onto AOL for the first time on the family computer. Your mom brings you some chocolate milk. Everything is alright in the world.” genre feels like it’s just half a goose-step away from the “This is what they took from us” and “We used to be a real country” posts.

Manley goes into frogposting much more deeply than I can here, and I really do encourage you to read the whole essay if you have time. But one of the key points that Manley makes — and the one that most stuck out to me — is that the type of escapism we find ourselves drawn to can tell us more about ourselves and our needs than what we’re trying to escape in the first place. What are we looking for? What are the needs we’re imagining being fulfilled? Why aren’t they possible in our current circumstances — and what would it be like if they were?

What forms of escapism are you most drawn to, and why? What do those escapes bring you that the “real world” doesn’t? What does it feel like to indulge in them, and, conversely, what does it feel like when you emerge back into reality? Can those two worlds be reconciled? What would it be like to try?

Prompt: Spend some time with your favorite form of escape — whether it’s frogposting, fantasizing, movement, movies, or anything else. Pay attention to what happens in your body before, during, and after you come back to “real life.” Create about it.

“Congressional Candidate Kat Abughazaleh on Parable of the Sower, and Her Love of Sci-Fi” (James Folta for Literary Hub)

In a lot of ways, Kat Abughazaleh’s campaign (she’s running for Congress in Illinois’ 9th District) reminds me a lot of Zohran Mamdani’s. It’s playful and good-humored and clearly principled, but also purposefully hopeful — optimistic in a way that we really, deeply need right now. So maybe it wasn’t a surprise that when a trend started going around BlueSky asking what book you’d be sworn in on if you were elected to office, Kat’s was perfectly aligned with her campaign’s ethos:

For the record, I will be swearing in on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower after I’m elected.

— Kat Abughazaleh (@katmabu.bsky.social)2025-12-09T16:41:29.177Z

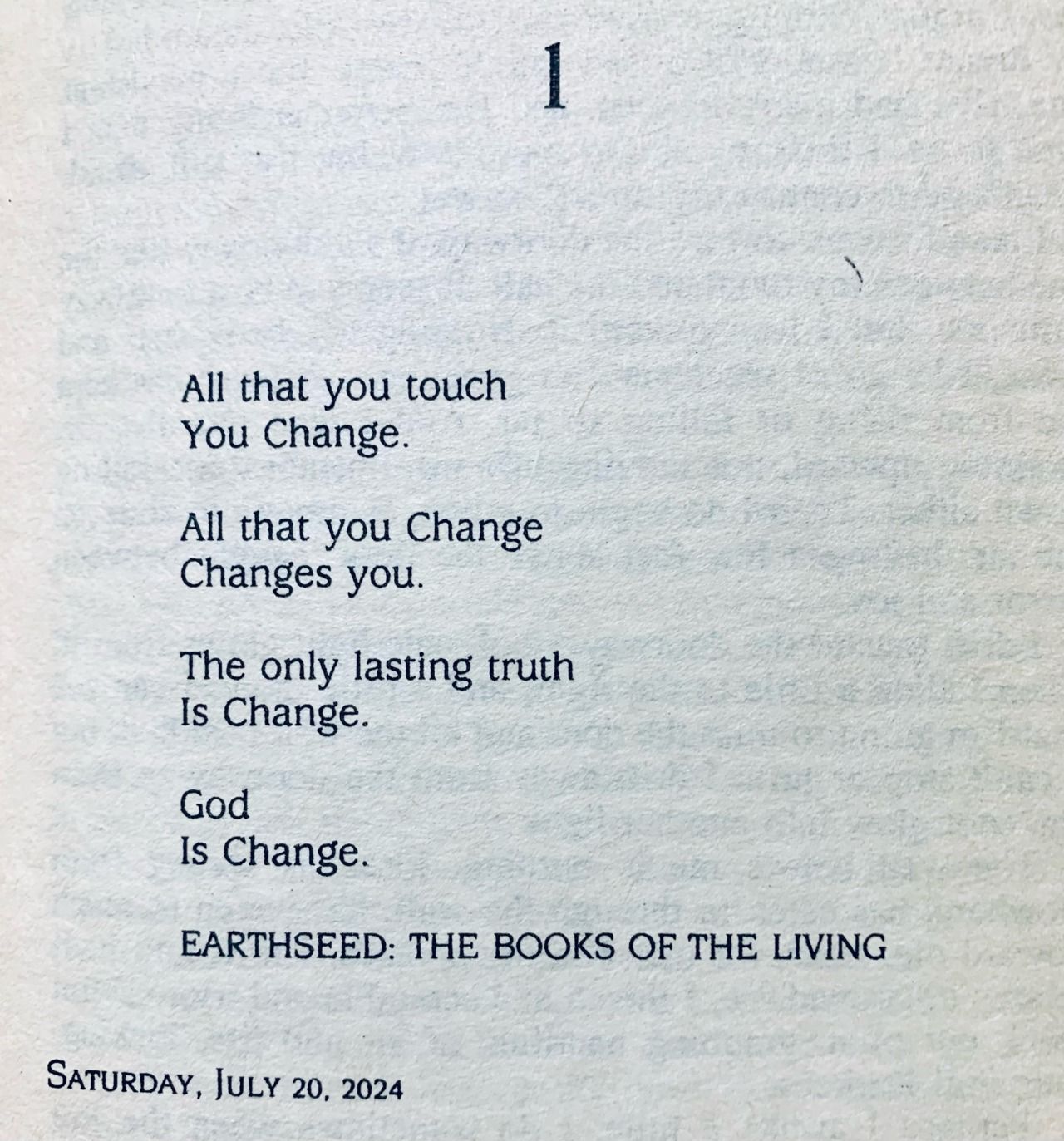

Parable of the Sower, for those who haven’t read it, is possibly one of the greatest works of science fiction ever written. It’s eerily prophetic, but also unexpectedly optimistic — much like Abughazaleh herself:

“Science fiction is so creative, and I am an optimist at heart. Even the direst forms [of science fiction] require some kind of optimism. Some type of looking forward.”

[sobs in “July 20, 2024”]

The whole article is worth a read — or, alternatively, you can listen to the podcast, which is equally excellent — but the point that Abughazaleh comes back to, repeatedly, is this idea of open optimism, of looking forward, of belief in change. She looks at this dystopian classic and sees “reminders of what we as humanity collectively can do and can be, how we can fight darkness through change, and how nothing lasts forever.”

In moments like this, when the fight ahead seems endless, that’s a reminder worth holding onto.

How do you feel about science fiction? What is your personal definition of the genre? Are there particular questions that you feel sci-fi should engage with or explore? What (to you) is required for worldbuilding in sci-fi in order to make it interesting, new, or exciting? Do you see the genre as ultimately optimistic, as Abughazaleh does? Why or why not?

Prompt: Jot down the first five titles — of any medium — that come to mind when you think of science fiction. What do they have in common? What separates them? Create about it.

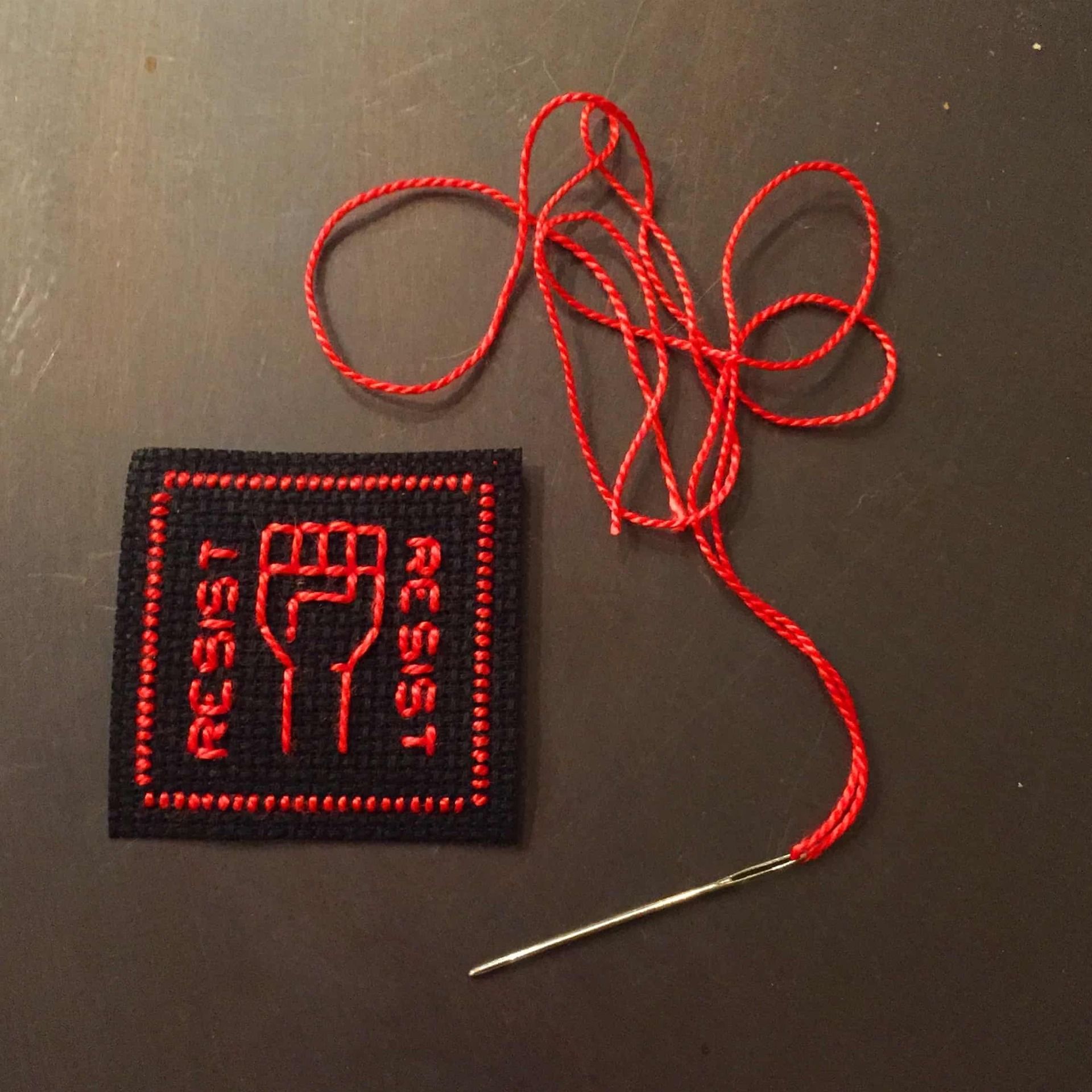

“‘Weapons of mass construction’: the US ‘craftivists’ using yarn to fight back against Trump” (Cecilia Nowell for Guardian US)

Every now and then, someone asks me why I take a broad approach to creativity in this newsletter, when it’s so obvious that my own focus is on writing.

The answer — other than my honest belief that I think every form of creativity is worth celebrating — is that just because my medium is writing doesn’t mean that I don’t see the power in showing up to the resistance armed with, for example, knitting needles instead of a pen or a paintbrush.

Articles like this one are a reminder of exactly that:

In early October, Tracy Wright invited a group of other women in her social circle – all fellow knitters — to gather outside the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility in their home town of Portland, Oregon. They were “armed with their weapons of mass construction”.

Donald Trump had just ordered national guard troops deployed to the city, which he called “war ravaged” in order to protect ICE facilities he said were “under siege” by anti-fascists “and other domestic terrorists”. Wright wanted to show that life was continuing as normal in Portland, and be a friendly face greeting any immigrants arriving at the ICE facility for appointments.

But “I didn’t want to go by myself,” she said. “I wasn’t sure what to expect.” So, she and the other women — who would eventually nickname themselves “Knitters Against Fascism” — brought their knitting needles and lawn chairs, and returned week after week.

The term “craftivism,” Newell writes, originated in 2003 with writer Betsy Greer, putting a name to the way in which “knitters, crocheters, sewers, embroiderers and other makers have long used their art to speak out against environmental degradation, racism, wealth inequality, fast fashion and other social issues.”

An embroidered work by Shannon Downey. Photograph: Courtesy of Shannon Downey |  At a fundraiser for the Chicago-based non-profit Project Fire, Downey raised $5,000 by selling embroidered works. Photograph: courtesy of Shannon Downey |  A stitching pattern by Shannon Downey. Photograph: Courtesy of Shannon Downey |

Resistance movements are tapestries, not single threads. To truly create change, we require cooperation, collaboration, and an understanding that no one type of involvement has more value than another. The person who provides childcare so that someone else can go to a protest is no less important than the protestor.

From the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who embroidered the white handkerchiefs they wore to protest against the disappearances of their children during Argentina’s military dictatorship, to the Aids Memorial Quilt, which wove together quilt blocks memorializing people lost to Aids, much of the success of those projects has been in the communities they have built.

“One of the big challenges in movement building is to build solidarity across different groups of people,” said Hahrie Han, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University and 2025 MacArthur Fellow. “At a certain point in the history of every social movement that has ever changed the world, there’s a point at which the movement gets challenged, or things get hard for whatever reason. And in moments of stress, the motivations that keep people together or that keep movements together are often their social-relational commitments, more than their commitment to the issue.”

The pink pussy hats of 2017 may have become a bit of a joke in progressive spaces these days, but when I see one out in the wild — before the cynicism sets in — my first association is still to remember how powerful it was to stand on a mailbox in midtown Manhattan (do not do this, I almost fell off and it was super embarrassing) and see an entire sea of them, stretching out for miles.

A piece of writing or a powerful mural may reach more people than a cross-stitch pattern or a work of embroidery. But what matters, as I’ve said consistently in this newsletter, isn’t what you make. It’s the act of making it. The energy that moves you. The values you’re trying to express.

The good you’re trying to do.

Do you see certain forms of creative work as more or less impactful in creating social change? Why or why not? To a similar degree: Do you see certain forms of resistance work as more or less important or valuable? Consider what types of people you associate with those particular forms of creativity or resistance, and how those value judgments align with your other values. Are they consistent, or in conflict?

Prompt: Choose a particular resistance or social movement, and do a deep dive into the types of creative works made by participants. What surprises you? Create about it.

”Let’s Talk About What It Means to Rest for the Sake of Rest” (Benjamin Schaefer for Electric Lit)

”Your body was not designed to swallow the whole planet’s screams” (The Earthly)

This being the last Friday Five of the year, it made sense to end not just on a slightly weird note (because obviously I had to go just a bit off-script) but also to end with a focus on something I hope we can all work on in the year to come: Rest. Real, intentional, impactful rest.

In his essay for Electric Lit, Schaefer takes a close look at the way he rediscovered rest as an intentional practice during the earliest days of the pandemic. He highlights ups and downs, pitfalls and triumphs, and ultimately comes to a place of equilibrium. One key idea he engages with is the concept of overfunctioning, which he defines as a stress response: “in moments of high stress, overfunctioners compensate: They do more, work harder, and take on additional responsibilities.” It’s a way, essentially, of keeping our brains so busy with Things that they don’t actually have to deal with the anxiety that sits beneath all the Things — which is, of course, a self-fulfilling prophecy in a way, since there are only so many Things we can do before we crash.

(I’m in this picture, and I don’t like it.)

Schaefer writes,

[M]y friend JoAnn would tell me that due to the near-complete cessation of road and air traffic during the shutdown, birds no longer had to pitch their songs in a higher and more rigorous register as they strained to be heard by their mates. I don’t know if that’s true, but I believe it. During my walks, the birdsong sounded lower and fuller. More relaxed, more melodious. I stopped to observe the Northern flickers that had returned with the spring weather. I watched the cowbirds roost in other birds’ nests. And during the rich slowness of one of those afternoon walks, the cause of my exhaustion became apparent. Unlike the birds, I had not relaxed. Even in the quiet solitude of the shutdown, I had continued to overfunction.

And, I realized, I had been overfunctioning for years.

He goes on,

The unexpected byproduct of the COVID shutdown was that, at least within my own sphere of influence and personal experience, the world had slowed down. The world had slowed down, but I had not. The contrast between the two had thrown the latter into stark relief. Once I saw what I was doing, I could not unsee it, and I knew that if I did not address the root cause of my exhaustion, the root cause of my exhaustion was going to address me.

What’s interesting to me about Schaefer’s essay is that it almost, but not quite, digs into the roles that capitalism, climate change, and collective grief play in not just creating but investing in that exhaustion. And that’s where the essay from The Earthly comes in.

This exhaustion is not weakness. It is a symptom of fighting on the terms of a system that thrives on chaos. If your hope feels gone, if you find yourself apathetic, it might be because your energy is being pulled in a thousand directions where it cannot make a difference. The corporations driving collapse know this. They profit when we rage online instead of organising in the streets, when we doomscroll instead of building solidarity with neighbours, when we feel so overwhelmed by the scale of it all that we forget the scale of what we can do together.

Where Schaefer engages with rest as an individual challenge, the writer(s) at The Earthly understand it as a collective one. “Rest,” they write, “must be part of the fight. Not retreat.”

Our suffering is shared, but so is our liberation.

The question is not whether you will rest, it is how. Will you let exhaustion bury you, or will you build rhythms of recovery that strengthen your resolve? The living world shows us how to do this. Forests fall silent in winter so they can explode with life in spring. Oceans breathe in and out with the pull of the moon. Resistance must follow these rhythms too. Burnout is what happens when we try to fight like machines. Rest is what happens when we remember we are alive.

Intentionally cultivating a practice of real rest might be something we undertake as individuals, but no matter how much I rest or you rest, we can’t create effective change unless rest becomes something we value as a collective. But — to get back to Abughazaleh’s words on optimism — to build those changes requires imagination.

But imagination is creativity. And that, of course, is what we do.

What is your relationship to rest? Do you think of rest as a physical act, or lack thereof? A mental one? Emotional? How does rest feel to you, and what thoughts, feelings, and sensations do you associate with it? What is it like to talk about rest? What would it be like to shift towards integrating more restfulness into your routines, your conversations, your community?

Prompt: So close your eyes. Imagine what you — what we — could build, if we were rested enough to make it happen.

Do not create about it. Just let yourself rest.

See you next week year!

💜Shelly