My loves, I don’t know about you, but my heart is so, so heavy this week.

It’s been a long, exhausting, devastating year to be part of the queer and trans community. Since the election last November, the constant awareness that not only does one major political party want to see us exterminated, but that the other — the one that claims to be on our side — is willing to throw us under the proverbial-but-maybe-also-literal bus in order to court right-wing votes has taken a toll on all of us, and it gets a little harder every day to show up to the work of creation with a sense of curiosity, wonder, and hope.

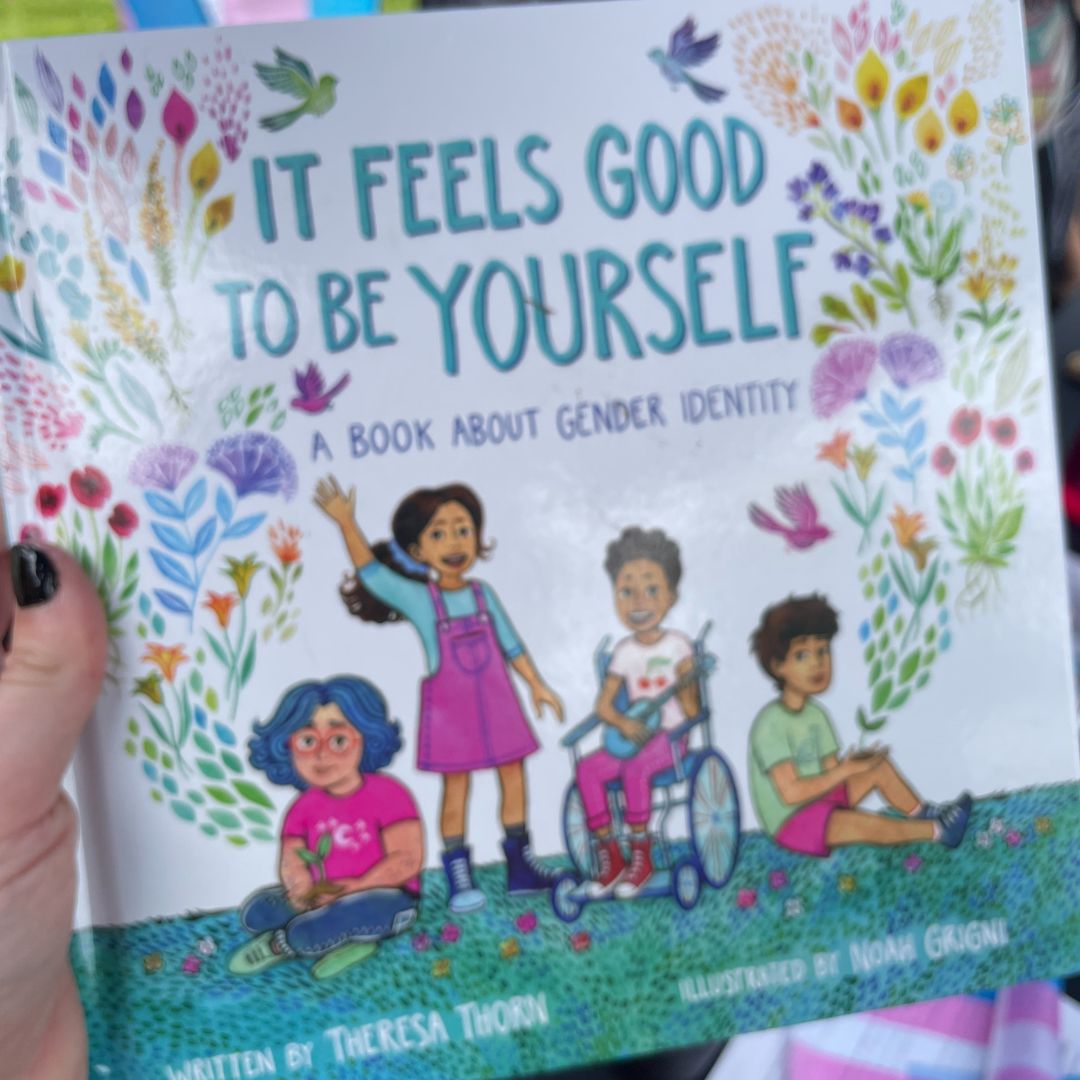

As the nonbinary parent of a trans child, this week has been especially horrible. The increasing attacks on trans youth over the past year, but something about this week’s votes and resolutions — including the House voting to advance a felony ban on gender-affirming care for minors, which only passed because of Democratic support — pushed me to a breaking point. Every time I look at my bright, brilliant, joyful child, my sweet girl with her wild energy and her total confidence that she is loved and perfect exactly the way she is, something inside me shatters at the knowledge that the care she’s already dreaming of might be slipping out of reach.

In “Good Bones,” Maggie Smith writes,

Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world.

I spend a lot of time, these days, wondering how much I should still be trying to sell my children the world. How much I should be keeping them safe from the knowledge that there are people who want to hurt them — for being Jewish, for being girls, for (at least one of them) being trans, for being part of a queer and trans family.

But I do, honestly, despite (despite, despite, despite) everything, I do still believe this place has good bones. I believe we can, as Maggie Smith says, make this place beautiful. I think that we have — as adults, as creatives, as humans on this wild and wonderful planet — a responsibility to use whatever resources we have to make a better, kinder future. I really, really do think we can do it.

But this week, my heart is heavy. If yours is, too, I hope you find some lightness soon.

your friday five!

this week’s highlights on creating for good

”The Only Thing We Have Control Over” (Megan Faley, resurrecting Andrea Gibson’s newsletter, Things That Don’t Suck)

As I wrote a few weeks back, when I’m emotionally exhausted, broken hearted, or just overwhelmed, I tend to turn to poetry. For years — and often still — Andrea Gibson’s poems were some of the first I reached for. They had, up until their very last days, a way of engaging with the world that I dream of being able to emulate.

“Excited” feels like the wrong word for how I felt to learn that Andrea’s wife Megan was going to continue this newsletter, but it’s probably the closest word to the truth. Because right now, it can be really hard to think about the things that don’t suck when everything kind of seems like it does. And yet, as Megan writes:

[I]t feels like our souls made some kind of agreement. Signed a cosmic contract. Because I could look at this time through the lens of this sucks. Of course it does! It is reasonable to find it difficult to train your eye toward joy and gratitude when you are widowed at thirty-six.

But I can hear Andrea whispering: No, baby. This is the perfect time.

Andrea often quoted their therapist, who said, “The only thing we have control over in this life is where we put our attention.” I know that to put my attention on all that is awful would be to have profoundly missed the point of all Andrea was guiding me toward, guiding us toward, in these last four years.

On days like this, in weeks like this, in cosmic moments like this, it’s more important than ever to think about where we put our attention. To turn towards the things that don’t suck: Community. Creativity. Curiosity.

Life, and love.

Where is your attention focused right now, and how does it make you feel? How much of your mental, emotional, creative energy is tied up in the exhausting terror of our daily news, of the stress of late-stage capitalism, of the weariness of existence? How is that focus impacting your creative work — if you’re creating at all?

Prompt: For one week, keep a running list of “things that don’t suck.” Review it each night before bed, and each morning when you wake up. Go through it again at the end of the week. Create about it.

”For Sylvia Snowden, Color Is Life” (Jasmine Weber for Hyperallergic)

One of my very coolest “six degrees of separation” connections is that one of my best friend’s father is a member of the Colour Research Society of Canada, which is totally focused on the science and communication and everything-else of color. Their description, which I think I would adore even if I didn’t do nonprofit comms as my day job, is “We are a community of colour interpreters, knowledge seekers and experts. Colour is our common focus.”

I love that! I’m very obsessed!

My perspective on color, generally is, “I like it!” If Millennial Grey has no haters, it’s because I am dead. But I’m not, by any means, any kind of expert. That’s why I always have so much fun reading profiles of artists like Sylvia Snowden, who have made a lifetime career of engaging with color. It’s a foundational part of her work, which absolutely comes across when you look at her paintings:

Sylvia Snowden, "Untitled (Purple Hand)" (2002) at White Cube (photo Jasmine Weber/Hyperallergic)

At age 83, she still paints every day. Her approach to texture, which she dichotomizes as both visual and tactile, has been developing since age four. She uses acrylic paint and oil pastels on masonite, an innovation born out of a residency in Australia, where she wasn't able to procure enough oil paint and knew her canvases would not dry in time to be shipped home. (Also, her children “could not stand the smell of turpentine,” she told me.) The resulting artworks are thrilling impastos, sculptural in quality. She has fittingly identified these detonations of color, which physically undulate from their surfaces, as “structural abstract expressionism.”

When I look out my window, the general vibe is all greys and browns and whites. When I turn my head to look around the room I’m writing in, I’ve surrounded myself in color: rich green walls in this room, bright yellow in the room adjacent, colorful pillows, even the hot pink of my dog’s collar. It’s a room that, no matter how shitty everything else feels, makes me feel a little pang of joy.

That, my dudes, is some magical stuff.

What is your relationship to color, and how does color manifest in your work? Are the metaphorical curtains “just fucking blue,” or is there an underlying symbolism or intention in the way you use color to set a mood or convey a theme? Are there particular colors you associate with different aspects of your work, your process, your own emotional or mental state? Has that always been consistent, or have your feelings changed over time?

Prompt: Visit a Random Color Generator and generate either a single random color (or, if you’re feeling fancy, a full palette). Spend a few minutes sitting with your color(s). What is your instant reaction? What feelings, thoughts, or associations come up for you? Create about it.

”The Vanity Fair photographer who disrupted Trumpworld’s polished image” (Shane O’Neill for Vanity Fair)

So like…here’s the thing.

Sometimes, we create things out of love. Sometimes we create things out of anger, or frustration, or joy, or grief. Sometimes we create things just out of the pure delight of creation itself.

And sometimes, we create things out of pure fucking spite for the people in power.

In case you’ve been off the internet the last few days (if so, please teach me your ways), on Tuesday, Vanity Fair published an interview with Susie Wiles, Trump’s Chief of Staff. In addition to some truly unhinged remarks about the administration, the article was also accompanied by photos taken by veteran photographer Christopher Anderson. And y’all, those photos are. Something.

(Don’t worry. I won’t jump-scare you by adding them here. This is a safe space.)

What made the photos so astonishing, especially — as O’Neill points out in his interview with Anderson — when contrasted with Vanity Fair’s usual “dreamy” aesthetic, is that they don’t go out of their way to make their subjects look like anything other than what they are: fallible, imperfect human beings. No airbrushing. No extra posing. No taking away the blemishes or the injection marks (looking at you, Karoline Leavitt) or tweaking lighting to make people look, and interpret this word however you’d like, better than they are. But what makes Anderson unique, really, is that despite the potential for doing so, he didn’t make those choices out of spite — at least, not that he’s saying:

[…] Some people are reading this as being an attack or being petty.

If presenting what I saw, unfiltered, is an attack, then what would you call it had I chosen to edit it and hide things about it, and make them look better than they look? […] My job is to go in and draw on my experience as a journalist and photograph what I see. I go in not with the mission of making someone look good or bad. Whether anyone believes me or not, that is not what my objective is. I go in wanting to make an image that truthfully portrays what I witnessed at the moment that I had that encounter with the subject.

The conversation that’s emerged around those photos has been fascinating. Anderson has been accused (as O’Neill mentions) of being petty, of intentionally making his subjects look “worse” than they do in real life, of purposefully setting those subjects up to be mocked by the public. But what O’Neill is saying, with those photos, isn’t this is what you look like, take it or leave it, but something, I think, much more personal: This is who you are. This is how people see you. And fixing that for you is not my job.

Were there moments that you missed? Anything that happened that’s on the cutting room floor?

I don’t think there’s anything I missed that I wish I’d gotten. I’ll give you a little anecdote: Stephen Miller was perhaps the most concerned about the portrait session. He asked me, “Should I smile or not smile?” and I said, “How would you want to be portrayed?” We agreed that we would do a bit of both. And then when we were finished, he comes up to me to shake my hand and say goodbye. And he says to me, “You know, you have a lot of power in the discretion you use to be kind to people.” And I looked at him and I said, “You know, you do, too.”

What are the expectations that come with your field of creativity, and how strongly do you feel about adhering to them? Do you feel like you have a responsibility to fit within those expectations? If so, who assigned you that responsibility — and what, if anything, holds you accountable? What happens if you go against those expectations or conventions? Have you ever tried?

Prompt: List three expectations you think you’re beholden to as part of your field. For each one, consider what it would look like to purposefully defy those conventions. Create about it.

”on artistic effort and endurance in the age of AI” (Jeanna Kadlec for her newsletter, Astrology for Writers)

In case it wasn’t abundantly clear based on my everything, I cannot fucking stand AI. I could go into the reasons why — it’s horrible for our brains, it’s horrible for the environment, it’s racist, it’s literally killing people, etc etc etc — but let’s be real, we don’t have enough newsletter space for that.

(Do not even get me started about how AI models training on existing work now has people coming for my beloved em dash. You can pry that shit out of my dead, cold hands.)

What I will say, however, is that one of the most infuriating arguments people give me in favor of AI is that it helps them create. First of all, no it fucking doesn’t. When you throw a prompt into ChatGPT, you’re offloading the best part of creation — the hard, messy, work of it. And that’s exactly what my friend and teacher Jeanna Kadlec shared, in a newsletter she originally sent last year but re-shared this week:

I think a significant appeal of AI is that it shortcuts the discomfort of the creative process: the sitting in the muck of it, the not knowing what to write, the mistrust of self that inevitably impacts the trust of one’s art. The connective tissue in a book-length work that reveals itself over time. The years of taking one direction only to pivot on a project last-minute. The aha moments, when shit finally comes together in your body, the somatic knowing of goosebumps when you finally realize the way different characters or plot threads are intertwined. Being so deep in the work that you lose your “I,” when the immensity of the flow current takes you somewhere else.

What makes the creative process so wonderful — and part of the reason I started this newsletter in the first place — is that it is, inherently, an exposure of the self. It’s embodied, in the sense that it requires neural activity and memory and soul-deep input that is perfectly unique to each and every one of us. No two people can write the exact same short story, the exact same poem, because even if, in a monkeys-writing-Shakespeare sort of way, they managed to come up with the same combination of words, there’s something different and unique behind them. It’s not, as some people have said, that AI creates bad (read: poorly constructed, poorly executed, etc) work — though, in my opinion and many others’, it does. It’s that the work itself is empty. It’s missing, as Jeanna so beautiful puts it, those goosebumps. That flow. That breathless connection with the act of creation itself.

Make bad art. Make art that won’t go anywhere. Make art that will never see the light of day beyond your own hands. But make something. Make it yours.

gold stars for all!

What, to you, is the most meaningful part of creativity? What would it feel like to have that aspect of your process taken away? What would you say if someone told you that a computer could do it “for you”? What conversations are happening in your creative field about the use of generative AI? How do you feel about them?

Prompt: Think back to the very first creative skill you learned. Maybe it was baking with a caregiver, or coloring, or playing with Play-Doh, or making up little songs for yourself, or even dancing. Imagine an alternative future in which those first creative steps were replaced by an interaction with a screen, a chat bot, or an app. Create about it.

”Rob Reiner’s Death Was a Tragedy. His Life Was the Opposite.” (Brian Phillips for The Ringer)

The Princess Bride is one of those movies that I’ve seen so many times I can recite the full movie from memory. It was one of the movies that I was most excited to show my own kids (and it’s one of my almost-six-year-old’s favorites, now, too).

I don’t have a great write-up here, except to say that Rob Reiner was a true generational talent — one whose work came from a deep love of creativity, character, and kind-hearted humor. It’s telling that almost every story that’s come out since Reiner’s death has been one of a man who went out of his way to be kind, to be helpful, to make a difference for the better in an industry that’s infamously great at turning people into assholes.

I hope that I can come to see his death the way his films see death in general. One of the things that makes his best movies so special is the way they layer small-scale, everyday reality with the big capital-letter Motives that drive Hollywood story arcs. True love, but also corned beef on rye; a miracle, but also a sandwich. The human experience is part childhood quest and part bewilderment over Goofy. Neither of these things overwrites the other. Being a realist and a humanist means understanding that tragedy exists and that cherry-flavored Pez taste delicious. Death, in Reiner’s movies, is always there; so’s all the life and fun and silliness around it. To see them both clearly and choose to focus on life and fun was one of his achievements; I hope we can follow his example.

I don’t have a question or prompt for this one, just an invitation. As Wesley says in The Princess Bride, “Death cannot stop true love — all it can do is delay it for a little while.” Death can’t stop us from honoring a memory or a legacy, either. If you, like me, are mourning this great creative spirit this week, I hope you’ll also join me in channeling that grief into something good.

See you next week!

💜Shelly

P.S. If you have the means and the motivation, and want to support an organization that’s doing real on-the-ground work to support trans, nonbinary, and gender-expansive youth and families, my local org, Translate Gender, is doing exactly that here in Western Mass. They’ve been an incredible resource for us, and really need support right now. You can make a one-time (or monthly!) donation here!