- Creativity for Good

- Posts

- connection is the antidote to despair

connection is the antidote to despair

creativity q&a with jeanna kadlec

In the weeks since the election, one of the loudest conversations I’ve heard people having is about forming connections, and leaning into community.

In many ways, this is a very different take on the incoming Trump administration (boo hiss etc) than we saw in 2016. Eight years ago, the emphasis was on coming together in protest, loudly and furiously and determined. Today, the energy is focused less on making a splashy impact, but in a deep, human, genuine yearning for connection. To do something, however small, with someone else, in a way that says, “You’re here, and I’m. here with you. I see you, and you see me. We’re stronger together than we are apart.”

When we’re extremely lucky, these communities happen organically — via a street-side meet-cute or a spur-of-the-moment decision to help someone in need or a smart best friend who matchmakes us to the perfect local gathering spot. But far more often, these communities are built, with care and intention, by teachers who bring their own wisdom, their own experience, and their own gentle encouragement toward showing up, however that happens to look.

Some of the most impactful communities I’ve found myself in have been curated by my friend and teacher . In addition to writing the newsletter, Jeanna is a teacher of astrology, craft, and the interconnection of the two. She and I chatted over Zoom about writing routines, the connection between capitalism and why we only feel good when we’re burning ourselves out, and finding antidotes to despair when we need them the most.

creativity q&a with jeanna kadlec: creativity, relationships, community, and showing up

Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length, because Jeanna is so smart and I could have talked to her forever, but sadly Substack caps me at a certain number of words. Booooo.

Tell me a bit about your relationship to creativity and creating. What has that journey been like for you?

My relationship to creativity is very much a lifelong relationship — a lifelong friendship, a lifelong partnership. And I think that like any lifelong relationship, it has changed significantly from the time that I was a child, through my college years and my early twenties and my Saturn return. And then today finds me with my 37th birthday next month, I have one book under my belt, and I'm getting married soon. It's very interesting to me that at this point in my career, creativity and creative help, getting unblocked creatively, figuring out a sustainable creative practice — those are things that people come to me to help them with. Because I think I only ever feel like I'm, you know, stumbling in the dark, and only able to see five feet ahead of me. But somehow, when I write about my own experience with that, people are like, "Oh, I want to talk to you about that. And you can help me with that." I think I'm just very stunned that folks continue to come to me for this, in part because of the ways that I still feel like I'm just muddling through.

One of the major lessons of my adult life, especially one of the major lessons of my thirties, has been divorcing my relationship to or uncoupling my relationship with creativity from my work as a creative professional. Because your professional life and, you know, having a book out or having done a gallery show or any of that, that is not necessarily reflective of how you feel about your creative work. That's the output piece that I talk about with people constantly, but then there are the questions like, where's the input piece? Where's the relationship? Where's the spirituality in it?

That's the other thing for me — the older I've gotten, the more I've realized how deeply my creative work is linked to my spiritual practices. And a lot of my writing, like in my newsletter, is dedicated to really untangling that and better understanding it.

One of the things that I've really appreciated about working with you as a creative professional is the way that you approach framing creative work when you're working with other creatives. You introduced me to the idea of uncoupling, you know, a writing practice from a writing routine, and shifting the focus really from productive output to something that's more about forming a relationship with your creative work.

That's a lot of what I do in client sessions. A lot of people think that they want a schedule, they want a routine. And it's like, that's not sustainable. A schedule is going to change if you move, if you change jobs, if you have, you know, if you have kids, if Trump is elected — like all of these things are going to radically change the energy that is available to you every day for a schedule. So schedules are not sustainable, but practices are.

One of the things I find interesting is that so many folks also tend to come to me idolizing their college years. And the thing about that, it's like if you were taking a creative writing class, that was your job. That was your job. You were fed by the college cafeteria. You maybe had to do your own laundry, but you weren't cleaning a house. You didn't have many bills. Some folks, of course, are working their way through school and have responsibilities, things like that. But for most of us, that will never happen again, that time when you could have the same routine just focused on your creative work, without life interrupting you to do life things. A writing residency is the closest you're going to get to that again. And even then, you still have rent or a mortgage.

I think about that all the time. Not to go all Avenue Q about it, but there's that wistfulness of like, life was so simple! All I had to do was show up to my little workshop with my little printed stories. That was great.

Yeah, and I don't want to overgeneralize here because obviously there are a lot of folks, some of whom are in my life, who grew up with tremendous amounts of responsibility or were raising siblings. So obviously, I want to caveat that there is the group of college students who did not have that college experience. But for those of us who generally did, it's like, we were all friends. We were children. We did not know what we did not know.

I mean, I knew nothing about how publishing worked. I was like, publishing happens in New York, and that's all. I didn't know about the publication process, or getting an agent, any of those things. But I think that ignorance allows a lot of people to just spend time with the work, and just be like, maybe it'll be a book someday. And that's a very different emotional place to be operating from than like, I'm 35, I'm 45, I'm 55, like, you know.

And then somebody on social media shares the writing schedule of, you know, someone who gets up at 5am every day and like, writes for three hours and then swims fifty miles, or whatever.

Yeah, those are the outliers. The Stephen Kings and the Nora Robertses of the world are different.

Right. I mean, I think about writers like Ursula K. Le Guin and like, did she have my dream schedule? Sure. Could I ever do that? No, because I've got kids who need to eat.

Right.

But I think, what I've really enjoyed about working with you is that you talk about creativity as a relationship, and you acknowledge that what you're doing and that your relationship with your work is going to ebb and flow, depending on what's going on and depending on where you are in the work and who else is in relationship to the work with you. Like, you know, your first project is just yours. It's just your baby. You don't have to share it with anybody. And then all of a sudden, you've got agents and you've got editors and you've got readers who have all of these expectations.

So something I've really appreciated about you as a teacher is your focus on encouraging people to look at their relationship to the work without all of those other voices. Which is why I think the containers that you create are so important, because for like those two hours a day, whatever it is, it's just you and your relationship to the work, and not those other voices.

So, thank you for that reflection. First off, I really, I really appreciate it. Like as I started off — what a good way to start off my own interview being like, I don't know why people work with me — but that's that also like that imposter syndrome difference between like the professional and then the personal creative stuff.

I think that the approach I have is informed by many years of being in workshops myself. I wasn't a creative writing major, but I was a creative writer who was an English major. I was the editor of my college's literary magazine for several years. I did a lot, and I was in a lot of those spaces, and I didn't like a lot of it. Part of the reason I didn't take a lot of creative writing classes in college was because I took one and I didn't like it. It didn't feel supportive. It was, you know, the Iowa Writers Workshop model — the person getting workshopped is in the box, and they're silent, can't speak on their work, can't express their viewpoint.

It's so patriarchal. I hate it so much.

It's deeply patriarchal! It was also so focused on emphasizing line editing, but there wasn't a lot of room for experimenting with structure, which I really liked doing, or for experimenting with genre. And of course, my experience with this largely being an undergrad, it was a lot of people who hadn't processed their own positionality, like myself. So there's a lot of, you know, I don't relate to this character written by a black writer, that kind of thing. I think I came away with it thinking, like, this can work for some people, but I'm just going to be a writer doing my own thing.

And I think over the years and through building relationships with other people who were taking their work really seriously, but who also — very notably — were all women who were mostly queer, many of whom were interested in spirituality, really started to inform how I thought about, you know, how do we do this in a sustainable way? How do I write in a way that isn't like berating myself if I don't hit 500 words a day or without whatever the arbitrary word goal is? I think it took me a really long time to understand that under capitalism, and part of the way capitalism hypnotizes people, and keeps them locked into the system, is with the idea that you're never productive enough. And that your worth is determined by what you produce.

But productivity and production are actually, in an artistic field, very arbitrary things. Like, it's not a factory, you know? One of my uncles worked on the line for Nestle for like 30 years. He worked in a factory in Iowa, and he had a very clear clock, in clock out schedule. But with art, there's no clocking in, no clocking out. There are boundaries, but there's no like I'm on, I'm off, the art stops, it starts.

It doesn't work the same way. And it took a few really serious health crises for me to really start to come to terms with the fact that working all the time and expecting myself to be hyper-productive every day, was both burning me out and was bad for my health. And as I got deeper into my first book, and into especially into the professional part of it, where it's I had an agent and then we went on submission and like I got an editor and all of that, it took me a while to realize that I was really still working and putting the same expectations on my creativity as I had put on myself during graduate school.

I spent a really long time in a PhD program, and anyone who's ever been in graduate school knows there is no off switch. It's like, you wake up, you do your reading, you go to class, maybe you teach a little bit, you go sit at a coffee shop for eight hours with your friends, and you write your papers and you grade your students. It's just constant.

While your soul crumbles around you.

And your soul also crumbles around you. And I just didn't have an off switch. So it took a really long time for me to develop one, and in many ways, life forced me to develop one. I started to realize that that way of being in relationship with my work was not healthy. Until my appendix burst, and I was hospitalized for a number of weeks. It really held up a mirror to what I was doing. I almost died, and even when I was home with Meg, I couldn't move, I needed help going to the bathroom, I passed out really easily.

Like, it was really rough. And my appendix burst the week that my final edits were getting turned into my editor. And my editor, Jenny Xu, is of course a humane, wonderful person, and she was like, "Oh my God, you're in the hospital, this can wait." You know, take care of yourself. Not all editors would be like that. But Jenny was, and my agent was, and my writer's group — everyone was like, Jesus Christ, calm down. Like, you're high on morphine. Why are you texting us about your book? Like you're on a morphine drip in the hospital. Like stop thinking about the book.

And I just was so deeply depressed and miserable. I was like, I'm not productive. I'm not a good person. And like, took a little bit there for conversations with Meg texting, like with my sister and my writers group to be like, that's not normal. Or maybe it is normal, but it's not good. Like, my, I almost died. Why do I think I'm about to finish a book? Like, why am I putting that expectation on myself? That's very silly, actually.

So that experience of just a few years ago, honestly, is what really started to prompt me to think about more sustainable ways to honor my relationship with creativity. Also in hindsight, when I looked at it, I was still being creative in the hospital. Like, one of my friends brought me coloring books and markers. And so I was coloring, I was watching The Witcher — like, Meg was crawling into my hospital bed with me to watch The Witcher and like talk about fairy tales. Like, in hindsight, I was still being creative because I'm just a creative person. I was still engaging with creativity. I was still being creative. I just wasn't doing work that was going to pay me. And those are very, very different things.

It reminds me a lot of, you know, Ross Gay's books of essays on, you know, inciting joy and finding moments of delight, not to do anything with them, but just to experience them. Because, that's the capitalism thing, right? It's not creativity as creation, it's creativity as productivity. Whereas looking at this framework of creativity as active noticing or creativity as active engagement with stories and with the world and with your relationships — but even then, I notice myself trying to justify it as being part of generative, productive creative work. And it's a challenge to remind myself that that's capitalism talking.

But like, why is a word count more generative than taking a walk and thinking about my characters, or working on a mood board or, you know, finding the right songs that represent a scene to me? Why is that, why do we think of that creative work as something that's not generative? And it's because we're brainwashed by capitalism and capitalism is bad. Which I honestly think could be the subtitle for this entire newsletter.

You know, it makes me think of one of Mary Oliver's lines, that attention is the beginning of devotion. What we pay attention to, what we spend time with, that is what we're devoted to. And I remember when I read that for the first time, it so reminded me of scripture about idolatry, because of the evangelical background. Because it's the whole usual, have no other gods before me idea that is very, you know, at least within evangelical Christianity, everything should be about the Church.

It gets used by churches as like, this is why you should spend more time volunteering with us. This is why you should give us more money, because what you put your money to, what you put your time to is your God. And obviously the Church is God. And evangelicals clearly have not quite taken those lessons to heart in the same way I did because like Trump is clearly their God, but that's a different topic. But when it comes to creative attention, that's the spirituality. That's the relationship.

Oh, we love Mary Oliver. We love her. I think that I say all the time.

We do love her.

Speaking of spirituality, can we talk a little bit about your work as an astrologer and how that plays into your creative work and your creative process, but also the way you teach and build community?

So I've been doing the Astrology for Writers newsletter for about five years. And in many ways, it was an outgrowth of some commentary that I had been doing on Twitter back in the day. This was like, circa 2017, 2018. I was really seriously learning about astrology, and because I was a writer, I just started refracting it through that lens. I did a whole article for Electric Literature about like your author horoscope back in the day, like, you know, using different archetypal writers who have those signs as, you know, the example like James Baldwin is a Leo, Mary Oliver is a Virgo, Margaret Atwood is a Scorpio. I did think I did Lin-Manuel Miranda as the Capricorn. And he really is just the ultimate Capricorn writer. Why do you write like you're running out of time, etc, etc.

Like, it's very there. So I did, I did an article on that, Electric Lit then asked me to, you know, kind of come on and do horoscopes for writers specifically. And so the newsletter very much was an outgrowth of that.

But I think what you're talking about with how my teaching has developed over time is that when I started getting into astrology, I was still very strongly embedded in that, capitalist mindset that we all are, but like for me, it had been delivered primarily through academia, which is you know, you are your work, you are the quality of your work, are you contributing anything new to the field, how much are you sacrificing for this? And the more I got into astrology, the more I started to slow down.

Again, this did not happen right away. This happened over time, and like I said before, health crises were a major part of that. But astrology had already started to slow me down. I mean, even just looking at the cycles of the moon, and that's that's a place that I often encourage folks to start with, because to my mind, it's a place where that's a really natural meeting point with a more animistic understanding of the world. The moon has two weeks of waning, new moon, two weeks of waxing, full moon, two weeks of waning before we circle back to a new moon. The moon increases, but then has a period of like rest and letting go and release and process. Like, the moon is just not always growing, growing, growing. And neither are we.

So it felt like it was a very natural meeting point. I felt like astrology is a symbolic language, but to me, there were very visibly, very practical applications and interpretations for life, which then proceeded to draw me more deeply into animism as a worldview and as a framework, and eventually started to draw me in and open me up to more deity relationships. I'd been really closed off to deity relationship after leaving the church, so understanding the planets themselves as embodied beings, which is not something every astrologer believes, took adjusting, but also was an opening to another type of relationship.

A lot of your teaching comes back to relationships, and I think that's part of what makes your newsletter so compelling. And that says a lot about you as a teacher as well.

You know, I think the way that I teach astrology requires participation. It requires the reader, the student, whoever's participation, in that I am not interpreting things. I really put a premium on free will. And this is also where I deviate in my own understanding from, from certain great luminaries of neo-traditional, reconstructed Hellenistic astrology, like Chris Brennan and Demetra George, both of whom I've learned so, so much from over the years. I've noticed that the longer that they're doing this public work, the more their work leans more into fate. And, you know, this idea of fate that I as someone who left the Evangelical Church and who's deconstructed, I have just such a knee jerk reaction to that.

There's so much in this world that we cannot change. So much about the way that we're born, like race, class, like whether we are in a space to express or explore gender or sexuality in an expansive way, like where you're where you live in the world, all the systemic bullshit that we all endure.

And in my mind, the idea that you have no control over how you understand those things, learn about them, interact with them, develop your relations, like, that is something that we do generally have, at this point, a lot of control over. So I really just put a premium on how much the interpretation of what something is doing in someone's life. It's like, well, what are you gonna now that you know this?

And that's somewhere where my work is not for everyone. Like, sometimes we people are just overloaded and flooded and they just want an easy answer. Like that might be a really fatalistic, really tragic thing that they're being told that they believe, but they're like, well, that feels like at least I know, like it sort of answers that yearning, that curiosity. At least it gives them an answer or a solution, however much of the bandaid it is. And it doesn't require further thought. It doesn't require further participation.

And because I am someone who, whether because of temperament, life circumstances, any number of things that have made me the person I am, if there is a way to explore something more deeply, if there seems like a different and better option, then I want to do that thing. If there's something that is a way for me to take more action or to live more in integrity, whether that involves me almost always being the person who says I love you first in a romantic relationship. Like, I think I just have a lot of activation energy that is often reflected back to me as courage. It never feels like courage in the moment. But those are the people who I fuck with.

And those are the people who my work is for. Someone who is more — I mean, this is gonna sound terrible, but like someone who is more passive or who kind of just wants to be told what to do, that person is not going to like me. But that's partly why I love the community that's originated around the discord around the newsletter, because my work attracts a lot of people who take action, and actually do shit, who take risks and who are willing to take big swings, and to really put themselves out there.

And, you know, just to be be really vulnerable and honest about it, like, I just, I don't know, I respect the fuck out of so many folks who I'm in community with through this work. Because we're all trying to live boldly, to be cliche about it. But right now, you know wallflowers need not apply. Like, this is the space where we are like, jump, we're holding hands and jumping off cliffs.

I think, especially in this particular moment, inertia is the biggest barrier. Inertia and despair. And I think that when folks are like, this is bad, the solution is to shut down. And the solution is to say like, we are doomed to X, Y, Z things coming down the pipeline that are scary and overwhelming and dangerous and threatening and do put us as queer folks, as medically vulnerable folks, in really unsafe positions. The easiest thing for people to do emotionally is to not engage with that fear. And to instead say, I'm going to require you to participate in something, in showing up, in engaging, in deepening your own understanding and deepening your own relationships to community. I think that that in and of itself is really bold work.

And you do it very compassionately, right? You don't frame the discord as, you know, this is a place where you have to like, show up and get in with your shit and go get shit done. But I think the energy that you create and the people who sort of come towards that energy are people who are looking to find ways to further participate in whatever they need to do. And I think in moments, right, like that we're in right now, I think that's the most important work that we're doing.

That's so beautifully said. I will say, since we're talking about the discord, like I love the discord, also because it's the place for softness. Yeah, for and for resting after you did the thing, or for your vulnerability and nerves and imposter syndrome, which like we all have about doing the thing, like it really needs people in every stage of that process. And so I really appreciate that that's a space where folks can really show up as their whole selves and not have to be— like you said, doing the thing, like that's what the showing up to the work containers for like, like, yeah, we're gonna write books, we're gonna do we're gonna show up to the page like that's I have spaces for that. But like, this is a more holistic space.

As we're talking about this, too, there are a few different things that are coming to mind that I do want to share that are things that are really old things I learned. I love old things. All the old things are new again. But that really informed just my perspective. And this goes back to when we were talking about the scheduling, but writing schedules as practices.

Like, I don't know if you, like me, were obsessed with writing craft books when you were a teenager. Like, yeah, you like you'd go to the Barnes and Noble or the Borders or wherever wherever and just like, post up. But I loved reading all of those, like The Art of War for Writers. But probably the singular most impactful book I ever read as a teenager was Barbara DiMarco Barrett's Pen on Fire. Let me find my copy — it's like, oh my God, it's so faded with sun. Okay, it's Pen on Fire: A Busy Woman's Guide to Igniting the Writer Within. God knows why I picked this up when I was in high school, but she's a busy woman. Like, she's a mom, she has fucking, housework stuff. But one of her core tenets is dismissing the fantasy of writing eight hours a day, and instead embracing the time within.

So she was like, writing while the water was boiling, writing on a pad while you're in line at the grocery store. She's really big on the idea of 15 minutes a day. And that like fundamentally shifted my brain. I was like, "Oh, I don't have to be writing in these long chunks. I can just write whenever for any amount of time." And I know that everyone's brains work a little bit differently and that some folks genuinely do need longer sessions to really sink in for sure. It just broke me of a lot of shame and fear I had around like, I'm not a writer if I'm not like having these long sessions at my desk.

It's funny that you bring up craft books because I'm reading Bird by Bird right now for the first time. But, you know, Anne Lamott talks about carrying index cards everywhere. And like those little things that you like, write down in the grocery store, you write down when you're on your walk, you write down while you're, you know, out in the garden, it's all important.

And like, I was always a person who was like, if I'm not like sitting at my desk writing like do I get to count it as writing? And especially since having kids, it's like, I write on my phone while I'm nursing at 2am, I write in parking lots, I write in bathrooms, like — I think that, you know, you get a lot less precious about what gets to count as doing something. Which I think that also sort of comes back to what makes the Discord community you created so special, because it really shows, you know, sometimes, sometimes showing up and doing the work means coming into the advice channel and being and like being like really open, like, "I don't know my neighbors, how do I introduce myself to my neighbors?" Or like, you know, "I haven't been masking as often as I should. Do you have any tips for getting back into this habit so that I can show up for my community in a way that is supportive and clearly engaged with, you know, what the needs are of the vulnerable folks in my community."

There's this expectation that activism is only one thing, organizing is only one thing, making an impact is only one thing. But what we actually see is that these movements are built up of very small conversations that ripple out into significant actions. And the containers and the spaces you created are really beautiful melting pots of those initial conversations that people are having to begin stepping further into that work. And I think it's because it encourages slowing down and engaging and showing up.

But also, sort of looking at those kind of micro-relationships that we have. and how those can become very expansive if we stop being fatalistic about it. Thinking to what you reflected back to me earlier about how so much of my work is about relationship, I think a lot of my work is not necessarily like the first on-ramp, but is an early on-ramp in terms of people changing their relationship, changing their relationship with their worldview, changing their relationship with their creativity, changing their relationship with spirituality. And it's been an honor and a privilege to get to build these different communities where folks then get to be in relationship with other people who share that.

It's a very common understanding that accountability, relationships, being in a friend group, being in community with people just helps the things you're changing to stick more. It's harder to get new habits to stick when you're in isolation, when no one knows about them. Not even that there's accountability, but knowing other people, having it modeled for you by other people, who you're like, oh, this person has kids and also does a new, whatever it is. This person has kids and is also a writer. This person is also processing their terrible, high-control religion experience and not finding new ways to express through astrology. I think the connection is the antidote to despair.

It's the antidote to inertia, too.

Yes. And I think I so appreciate that you use that word because when I think of dysfunctional family networks, or I think about my own extended family and how dysfunctional it is, I'm like, it's because it's a bunch of people locked into the same inertia — locked into the same ways of doing things. And the folks who give a damn enough to try to change it are the people like me who ended up being the black sheep. But when you're building something with other people outside of traditional natal family, outside of traditional workplace kinds of structures, that's also a creative thing because you get to make something new. You get to make a new system. You get to make a new way of being with other people. And it also takes the individualistic capitalist burden off of you.

I think that's what so many folks in this country are despairing. It's certainly what I have also been prone to over the last few weeks. Like, well, there's nothing that I can directly do that's going to stop this. And of course, the answer is generally, for most of us, not in what we directly just ourselves can do to stop this whole thing. It's what we're doing together. And for most Americans, that's a reframe.

Yeah. I mean, I think if connection is the antidote to despair, like community is the antidote to capitalism, right? Capitalism wants you to be isolated and so focused on individual production that you forget to form connections. And I think the more we engage in community, the more we're like, oh, these systems are bullshit, actually.

Yeah. This is very much like ten steps to the left a sidebar, but as someone who grew up super working class like comes from generations of poverty in this country. When I learned about the late 18th, early 19th century, when land owners started actively working to separate and divide the class solidarity between working class poor whites and black folks who were enslaved. When I understood that some of those earliest anti-slavery riots were joint efforts by the working poor alongside folks who were enslaved I was like, "Oh my god." Like, what a remarkable success of white supremacy that they divided communities from each other. They separated people who actually have a lot more in common with each other than they do with the ruling class. The work of white supremacy and capitalism is to make poor working white folks identify more with the ruling class than with other working people.

It's quite impressive what you can do with a ton of magic, with a ton of money and power and influence. And also the magic of the church. So I know that's like many steps to the left but like, I didn't learn about that until college. It was ages until I learned about that. But it was an "Oh, shit" moment. That they did it because finding connection with people, especially people who don't look like you or pray like you or love like you, that intimacy goes too far toward destroying that system.

I think that's the subtitle to this whole newsletter, honestly. "Love each other, do creativity, fuck capitalism." I should work that into the newsletter graphic. So, is there anything else you want to share about what's coming next for you? I mean, you're getting married — everyone support Jeanna and Meg's honeymoon fund! — but what else is going on?

Oh, that's so nice. And thank you. So yeah, Meg and I are going to Spain, which I'm so excited about, and this is in part because we had tickets to Greece earlier this year for a friend's wedding that we ended up not being able to go to and like having to cancel. And so we were able to rebook those tickets. Hooray!

For what I'm doing: I'm working on a book that's based on the newsletter, Astrology for Writers. So, you know, TBD on that. And then the other piece, and depending on when this goes up, it may be launched, but met my beautiful wife-to-be Meg and I are joining forces and are going to be hosting a very long-term creative container, specifically dedicated to the spiritual practices that can support folks working on creative projects. It'll be a six month long container next year.

Jeanna Kadlec is a writer, astrologer, and teacher whose work bridges the literary and the spiritual, the magical and the mundane. She works with writers and artists who know that creative living and the business of making a creative living don't have to cancel each other out. You can also follow her on Instagram and subscribe to her newsletter.

updates from shelly

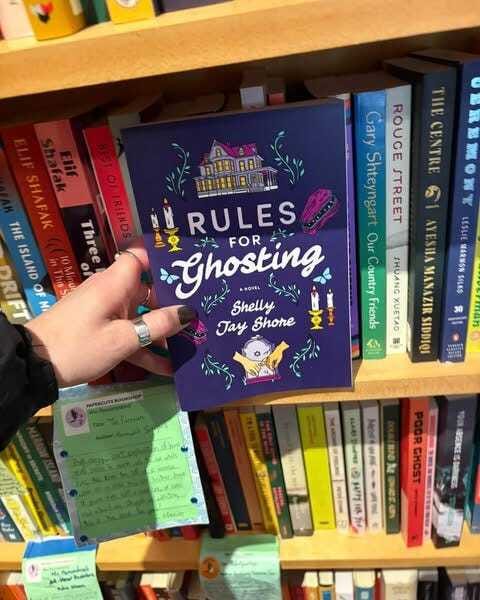

Rules for Ghosting has officially been out in the world for more than 100 days. Happy 100 days, beloved book! I’m still hearing from readers about the ways Ezra, Jonathan, and their many ghosts are helping them feel seen, process their own feelings, and even find some healing. To everyone who’s picked up the book, shared it with a friend, posted it on social media, or even just spent some time reading it — thank you, thank you.

Also, #ICYMI, my books are open for writing and editorial services! If you or someone you know is looking for a freelance editor, copywriter, query critique, or social media strategist, come hit me up! The prices on my website are a starting point — sliding scales and individual pricing is always a possibility. Here’s what some of my past and current folks have said:

Shelly has a knack for listening carefully and asking insightful and incisive questions to get to the heart of things. Beyond the session itself, her follow-up letters with summaries of discussions, exercises to keep thinking about possibilities, and reading suggestions have helped me make progress at a rate I hadn't dared to hope for before.

Shelly has taken our mission of fostering communal care at the end of life and developed strategic and creative posts, images, and writing that reflect the warmth, empathy, care, and wisdom we aim to share. We couldn’t have asked for a better partner.

Shelly helped me jumpstart my creative brain when I was recently in a writing rut with my latest book manuscript, and she completely turned my project around with her smart thinking and creative suggestions. Her advice definitely helped put me back on the right path.

Until next time. 💜

resources, links, and further reading

spotlight on: creativity, community, and showing up

read:

“In times of defeat, turn toward each other” Sam Delgado for Vox

“Here’s How We Can Help Each Other in Trump’s America (and Beyond)” Nico for Autostraddle

“Creative activism 101: An antidote for despair” Iain McIntyre for The Commons Social Change Library

listen:

“Why You Can’t Care About Everything” Diana Rose Harper on the Healer Dealer podcast

donate: